You should open this email and read in your browser, there are lots of movie trailers you may want to watch.

Before I studied history in college, if I wanted to know something I’d go to the library and bring home a stack of non-fiction books on a subject. I’d sift through various tomes and perspectives all written by experts. Surprisingly, the academic history program wasn’t really like that. There was an understanding that history, at its core, is an imaginative pursuit. Of course there were still several cited and peer-reviewed works; but complimentary to that, there was always an emphasis on fiction reading and film analysis of works created around the subjects or time periods in question. In hindsight, it seems so obvious that would be the academically sanctioned way to study things, because it allows a layered knowledge of a subject. It allowed my next reading of cited-source history to be that much more empathetic and imaginative. It helps in gaining a nuanced perspective on politically charged rhetoric we’re bombarded with on every scrolling screen we own. Knowing more about our past in order to think more objectively about our present requires not only a rigorous reading of non-fiction, but a rigorous attempt to engage with the art it has inspired.

With Everything Happening Now

With everything happening right now, I’ve been thinking a lot about the movies, music, and books that have shaped my thinking on race in America. This is a chronological list not by release date, but by when I first saw it. Most of these are films I’ve seen in the last few years, but a few go back to my high-school days and before. Looking back, they must’ve been pretty impactful for me to have remembered them in this way.

I excluded movies like Django Unchained (2012) and Black Panther ( 2018), because everyone has seen them. I also excluded some good ones like Remember the Titans (2000) for reasons explained below. Ultimately, the films that have had a lasting impact on me are the ones that have caused me to think about the subject in a broader way. I don’t think the films everyone has seen in their long theatre runs and talked about around the water-cooler at work do that. They can’t. They have mass appeal for a reason. They mostly play it safe. So what you’ll see here are films that don’t play it safe and films that aren’t top-of-mind to everyone.

I wouldn’t call these reviews or synopsis’s either. They’re more of a commentary or a highlight of the films’ effect on me. I’ve linked to reviews and other things that can help you decide if you want to view it. I obviously think all of them are worth viewing, particularly if you’re asking the hard questions of how did we end up here?

Boyz n the Hood (1991) & Juice (1992)

I’m putting these together because they left a similar mark. I used to stay up late at my grandparents house because they had one of those first generation satellite dishes that was big as a car and had hundreds of channels. I must’ve seen these gritty thrillers when I was twelve or so and they made something very clear to me. It is a very different world out there in LA or NYC than it is here in West Texas. It opened my eyes to the fact that there is another reality out there that I can’t begin to understand. And knowing the characters in these stories was almost a window into national nightly news where Tom Brokaw would come on and talk about gang violence in a boogey-man, if-it-leads-it-bleeds kind of way. Movies like these added some humanity to the “crime in America” media coverage of the early nineties. Not to say they justify senseless gang violence. Far from that, they illustrate a boundary between America’s haves and have-nots and they show how well-meaning people get caught up just trying to survive. Did you know Moses of the Bible killed a man with his bare hands? Wonder what nightly news’ narrative that would’ve been fit into if it would’ve existed.

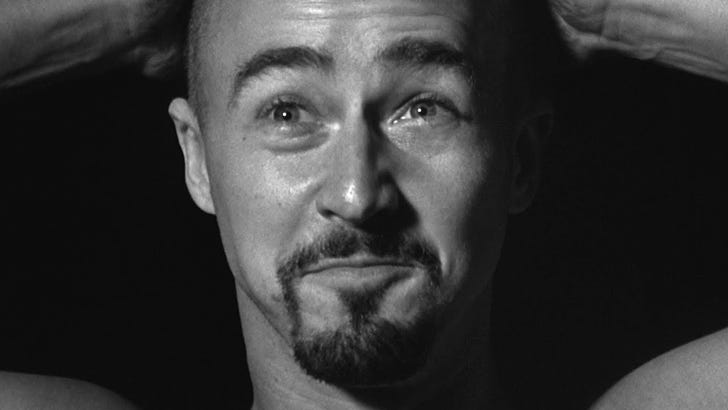

American History X (1998)

After Fight Club came out in 1999, I was on an Ed Norton scent. I picked American History X up at Blockbuster one Friday night sometime that same year. I would’ve linked the trailer here but I watched it and it’s just so dated and bad. The last time I saw American History X was probably 10 years ago and it held up well then, so don’t be deterred by the trailer if you happen to dig it up. The film is a profound, gritty work. I must’ve seen it 15 times and showed it to everyone I ever knew in my basement theatre in high school. I had a best friend once who told me that he and his family strongly disapproved of interracial marriage and dating. That was devastating to hear, particularly because I have two black siblings and I’m not exactly white myself. I’m not sure if this current MAGA era has returned him to that Neanderthalic state of thinking, but after seeing this film back then he admitted it had changed his mind about that. It’s powerful and one that will stick with you for a long long time.

Michael O’Sullivan Review and Synopsis

Cry Freedom (1987)

My friends, the Okogbo’s, showed me this about Steve Biko, the anti-apartheid activist in South Africa. I’m not sure if the film holds up but I remember feeling enlightened by seeing it so many years back. Years later I mentioned it to a circle of friends and one responded something like: yeah, but you know racism has really swung the other way there now, right? At the time it seemed like he was justifying the atrocities of apartheid because he’d heard of the current blowback violence in South Africa. But maybe he didn’t mean it that way. Either way, this was a film that made me question why this happens in humanity, not just America. Because the ‘why’ in South Africa is a different set of circumstances that have led to the same symptomatic oppression. It’s the first film that made me question the ‘why’ behind racism.

Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012)

Wow, this was an incredibly imaginative and engaging view. Half action, half fantasy. All heart. This, similar to Boyz n the Hood and Juice, pulls the curtain back to say there really are two Americas. This film is a truly joyous take on that reality, though. And if you want to know why Kanye West said of Hurricane Katrina, “George Bush doesn’t care about black people,” watch Beasts of the Southern Wild. To be clear, it’s fiction. It’s not that it’s true that makes Kanye’s statement accurate or even fair, but this film allowed me to see the context from which he was speaking. It allows me to understand the sentiment behind both the art and the statement.

This film is a great companion to David Gordon Green’s Criterion Collection work George Washington (2000). It’s a completely somber yin to the Beasts yang.

Mudbound (2017)

This along with Cry Freedom are the two most accessible films on the list. They’re most palatable for a wide audience. That’s not to say they’re innocuous because they’re still about the violence and subjugation inherit to racism. But overall, they have a more hopeful tone. This film is a powerfully staged and shot aesthetic beauty. It’s poetic and meditative around elements like the dirt and mud and rain and light. The cinematography is superb and is best viewed in a pitch black room with the audio cranked.

It seems to me that there are two perspectives along a spectrum within this history of race relations art. One is the perspective that we are all the same. We’re human. We share the same fears and the same aspirations. This perspective is true. The other side of the spectrum is to say: yeah, we’re all human— but things are vastly different between us. It’s not our similarities that define us as human. But it’s our differences. This perspective is true, too.

Take Mudbound for instance. It’s the story of two soldiers returning from WWII who deal with PTSD. One white and one black. Is it true that the same thing haunts them both, yes, if you mean the war. This point of humans sharing the same burdens is very clearly made. However, on the film’s portrayal of the differences, you need to look hard to see that the black man has no real home to return to after the war, except the actual dilapidated house in which his family lives- this point of their differences is a point made within the mechanics of the storyline. It’s not the focus. Their differences are a subtext. However, it does becomes a bit more prevalent with the plot’s development. But for those who don’t know much history the nuance could very well be lost. A deeper than high-school-textbook understanding of history related to the systemic racism of government programs like sharecropping and the Homestead Act is needed. Otherwise you can look and see equality where none exists. You can look and not see a context of systemic racism, rather a struggle between a single protagonist and villain.

This is the principle that makes Remember the Titans a better sports movie than it is a statement on injustice. As Ebert writes in his review of the film, “Victories over racism and victories over opposing teams alternate so quickly that sometimes we’re not sure if we’re cheering for tolerance or touchdowns.”

Mudbound does a better job at not oversimplifying it (if that’s what you’re looking for). Good art much like intellectual honesty lives in that tension between perspectives. This is the element that allows for a more hopeful vs. somber tone. Mudbound is more hopeful because it spends a bit more time telling us things from the similarities perspective, while not truly abandoning the differences. Contrast this with the work that is equally truthful yet heavier to bear, by someone like James Baldwin (whose film is featured next) who flips it. Reconciliation, to Baldwin, comes when people notice and appreciate the differences between black and white America. For Dee Rees, writer/director of Mudbound, reconciliation comes by finding our common ground, first.

If Beale Street Could Talk (2018)

A James Baldwin work turned film. This is a beautiful movie. The aesthetic is a dreamy one with a caramely-Harlem brownstone color palette that makes the greens, yellows, and reds of the set design and wardrobes draw you in to the films’ richness. It’s stylish as hell, one of director Barry Jenkin’s hallmarks. There’s a lot of dimension to this one. From wandering camera work that makes you feel like a breath of fall’s breeze through the borough, to tight headshots that break the fourth-wall with the story’s main characters; it’s equally dialed in to the blunt reality and breathy nuances of the human experience. The music score is an experience unto itself It’s a really hopeful orchestral arrangement with a jazz tinge. It perfectly matches the tightrope of expectations within the young characters. It’s a loves story, yes, but it’s ultimately about the idea that if we’re just empathetic and kind, maybe others will be, too. It doesn’t turn out that way.

I remember telling my wife, as the final credits rolled, this maybe the best movie I’ve seen this year. She said, “What?!” because of the way it ends. It’s definitely true to form for writer James Baldwin, in that it doesn’t get tied up into a nice little package for viewers. It doesn’t pretend. Watch this film on your biggest TV with your room as dark as you can get it, and your stereo as loud as it will still sound good. It’s an experience.

Sorry To Bother You (2018)

This maybe the least accessible film on the list—but I think it’s the richest, too. There are a lot of layers here, but at its core, it’s about class. That’s what this all about. Don’t kid yourself, this isn’t just about black and white. It may seem that way because of the news events that have cast that shadow upon the matter. But you can’t look into matters of race-based injustice very deeply without ending up squarely at the foot of larger ideas like colonialism and imperialism. Sorry To Bother You is about one such idea specifically: Marxism. For the purposes of this argument marxism has one central idea: free-market capitalism is prone to exploitation of its lower-class members. It generates and actually needs the vast inequalities it creates to sustain itself. I don’t mean to minimize the particular white/black flavor de jour of the American manifestation of this concept unfolding before our eyes because I do think racism is hideous, systemic, and very real. But I also think, much like Harvard’s Dr. Cornel West (and MLK before him) that it’s just a symptom of a much larger problem.

But it’s a problem that is easily obfuscated by reducing it into something that fits into a simple black and white binary rhetoric. If corporate America and media elites can have us chasing our tails to eliminate the American symptom: racism — then we’ll never see them continuing to line their pockets pulling the rigged-game’s lever that made race relations boil over in the first place. This is essentially what Sorry To Bother You is about. It’s not any easier to follow than that explanation… But it’s definitely funnier.

It’s brilliant. It’s creative and weird. It’s satirical and its emphasis on the materialism, commodification of everything (including protest), and the growing gap between rich and poor being the root of the problem is so nuanced and appropriate. It doesn’t deny that black people do indeed have opportunity in this country. It also doesn’t deny what parts of their “blackness” they might have to give up to participate and truly succeed in modern American society. But by the end, it makes it clear that all of us must give up certain aspects of our humanity to play the game on the world’s terms. It begs the question: if we think so little of our own value and personal worth related to what a materialistic culture tells us we should value- how could we possibly see the value or worth in someone who is different?

New York Times Review & Synopsis

The Last Black Man In San Francisco (2019)

This maybe the most aesthetically pleasing film on the list. It takes everything that Barry Jenkins did in If Beale Street Could Talk: the music, the cinematography, the stylish flair; and it adds a progressive and youthful cinematic arthouse flavor to it. It’s so damn hip.

It’s also saying a whole lot. It’s about the growing wealth gap. It’s about gentrification and what it means to be a black millennial male growing up in a whiter more homogenized-through-social-media culture. It’s about picking and choosing what we’ll hold onto in life. It’s about friendship and finding ways to embrace and support the differences between us. It’s about property ownership and the American Dream.

I keep saying a lot about the growing wealth gap. I think this film’s treatment of that subject maybe the easiest to digest. In the last 25 years, as San Francisco has sat neatly atop the tech-boom bubble and become one of the world’s richest cities, how do poor people there keep up with the rising costs of living? They don’t. Seems stupid to admit, but I thought SF was only tech-bros and millionaires now. But The Last Black Man In San Francisco shows what it could look like if you’re not either one of those and you don’t have resources or the desire to leave. The city is a character in this one, much like in an Alexander Payne film. It’s living and breathing and it gives you the sense you’re experiencing just like one of the main characters. I really loved this movie and expect really great things from the director. It’s another one where you can take it in its simplest form, as a buddy movie, and really enjoy it from beginning to end.

Reviewed (and panned) in The New Yorker

LA92 (2017)

Growing up in the 90’s meant a few key things: you wore black bicycle shorts under neon baggy shorts, you permed the back of your hair and spiked the front, and you watched cheesy TV shows every Friday night on ABC’s TGIF program lineup. You also probably remember being bombarded by three drawn-out media events: Operation Desert Storm, the LA Riots, and the OJ Simpson case. Every night Dan Rather or Tom Brokaw would come on and show a gamefied, propagandistic version of war in which all of America tuned in to see digital ‘Risk’ boards, montages of tomahawk missiles, and dusty tanks rolling through the desert a la Stormin’ Norman Schwarzkopf. About a year later we’d be bombarded with shots of LA’s skyline lit ablaze looking frighteningly similar to the Kuwaiti Oil Fires that occurred a year previous. And in ’95 the OJ Simpson freeway chase kicked off another media frenzy in which images of the glove-fitting, pictures of Nicole Brown, and various 911 calls’ audio would become common reference in American life.

The most shocking of the three were the LA Riots. The Rodney King beating. The Reginald Denny beating. The Korean shop owners who set up like snipers along the roofs IN AMERICA!? The images of police standing around arms-crossed as throngs of crowds looted stores right in front of them. This was pure mayhem and even for a 10 year-old like me, it seemed unbelievable.

LA92 is the best film I’ve seen on a subject that has been fascinating to me for almost thirty years now. There’s footage I’d never seen before and it all plays quite viscerally. It’s great editing and comprehensive enough that it shows a lot of context that is easily forgotten, but vital to understand if you want to think freely on the subject of race relations in America.

JustWatch LA92

You also must see O.J. Made In America (2016). It’s a masterwork of non-fiction filmmaking. And surprisingly it follows a narrative that everyone knew was there, but no one really explored in-depth until this film was made.

JustWatch O.J. Made In America

I Am Not Your Negro (2016)

Created from James Baldwin’s written work Remember This House. It was nominated for best documentary in 2017 but lost the Oscar to another important work: O.J. Made In America.

I was first turned on to James Baldwin’s writings in college. He was most prolific in the 50’s and 60’s, a time arguably more tumultuous than this for race relations. His writing is sharp and clean. It’s approachable and brings you in nice and easy. But it doesn’t stay that way. He hides the heft of the subject matter and you don’t know you’ve been walloped until it’s too late. His narrative style was a real inspiration for me in pursuing my own writing. A great writer makes you think, “I could do this.” But alas, I cannot.

I Am Not Your Negro is Baldwin’s personalized account of how the assassinations of three important black leaders struck him. MLK Jr., Medgar Evers, and Malcom X were all gunned down in the height of their popularity, but the film is not an assassination chronology- it’s his view of the history of the black man in America. It has a memoir quality as most of his essays do. This makes his work relatable. He recounts how his white teacher encouraged him early on and she was the reason he didn’t “hate white people”. He also recounts how white people ridiculed this teacher because she treated blacks with dignity.

Another thing about Baldwin’s work is that he infuses a heavy dose of pop-culture reference in his essays. He talks a lot about film. For instance, he was heartbroken as a boy when he realized his identity lied more accurately with the Native Americans than with his heroes, the cowboys, in all his favorite westerns. He also conveys the revolutionary import of Sidney Portier’s work and what his roles can tell us about America’s shifting perceptions of black men.

The film is complimented by a rich visual tapestry of stills and archival footage in a similar way to a Ken Burns film. With Samuel L. Jackson as the narrator, you can’t go wrong with this. It’s poetic, insightful, and shocking to see how far we have and haven’t come in this country.